The preponderance of the evidence indicates that protein is the most crucial macronutrient for the development and maintenance of muscle mass. Protein’s role in the regeneration of muscle tissue is undeniable, as it ensures that your body has the amino acid content required to repair the damage done to your muscle fibers following resistance training, and also after cardiovascular workouts and everyday activities that cause damage to your muscles.

With that being said, most recommendations and guidance that are provided with respect to how much protein you should consume on a daily basis are offered under the assumption that you are between 18 and 50 years old. The bodies of both men and women go through substantial changes as they age, and this can influence the varieties and quantities of nutrients they need.

So, when it comes to protein and the amount required to maintain a body that functions optimally — and maybe even a body that can grow some additional muscle tissue even as you age out of your physical prime — how much protein do you really need as you age?

Standard Guidelines for Protein Intake

If you ask a dietitian, they’ll usually begin their guidelines for adults by suggesting that you consume 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight. So, for a 200 pound individual, the baseline of 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight yields a daily protein requirement of 72 grams.

Granted, the caveat to this is the assumption that lean muscle tissue is what is either being preserved or built upon. That’s why other projections for daily protein requirements take a person’s body weight in pounds, divide that number by two, and then multiply it by a number ranging from 0.5 to 0.9 depending on how lean they are to get the needed amount of protein. Even using these ballpark projection methods, a fairly lean 200-pound person’s daily protein intake would land between 70 and 80 grams.

Athletic Guidelines for Protein Intake

Switching gears to recommendations for active adults and serious athletes, most dietitians will amend their advice to accommodate the needs of these groups. As such, the figure is boosted to 1.2 to 2.0 grams protein per kilogram of body weight. Therefore, presuming our same 200 pound test subject is an athlete, he would be advised to consume between 108 and 180 grams of protein daily.

For what it’s worth, there can be a wide range of differences between an active adult who works out moderately for 30 minutes four times a week, and an athlete who engages in two or more intense training sessions of an hour or more each day. Therefore, if you wish to adhere to the standard guidelines of a dietitian, the high end of the protein range probably only applies to you if you are engaging in well over an hour of training every day.

The Biology of Aging Adults

As you age, and especially as you enter your 50s and 60s, your body goes through a series of changes that makes protein consumption all the more critical. Among these are the degradation of muscle tissue — also known as sarcopenia — combined with a diminishing of your body’s anabolic response to protein intake, and a reduction in your body’s capacity to absorb protein altogether.

Because of these negative consequences of aging, an uptick in protein consumption is necessary to ensure that your body acquires all of the protein it needs, and to essentially guarantee that your body gets all of the protein it needs to maintain the muscle mass it already has, while limiting its deterioration.

Aging Adults and Protein

The point at which adults appear to be universally encouraged to adopt the protein consumption guidelines for older adults appears to be 65. However, there appears to be little agreement on where the upper range of the recommended daily dose of protein truly is, as the range for older adults can be anywhere from 1.0 to 2.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, without much offered in terms of a plan for escalation.

Please keep in mind that it would be a drastic leap in recommended daily protein intake if you were to leap from 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day all the way to 2.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight. If your minimum recommended total had been 80 grams of protein per day, flipping a switch and increasing your intake to 160 grams of protein is a dramatic jump.

One recommendation might be a gradual escalation of minimum protein intake starting at age 50, so that arriving at a daily intake of 2.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight by age 65 represents less of a macronutrient surge. Another recommendation could be to consume more protein on a regular basis at an earlier age, so that protein intake in the older adult range doesn’t deviate sharply from intake during earlier years.

Protein Safety

Recommendations for protein intake have been publicly proposed and debated for well over 60 years. For example, in 1960, The Houston Chronicle’s agricultural editor Elmer Summers informed his readers that men required 70 grams of protein per day on average, while women needed 58 grams, and pregnant or lactating women were encouraged to consume in the realm of 78 to 90 grams of protein daily.

Please keep in mind that the average weight of an American man during this period was 166 pounds, which is at least 25 pounds lighter than it is in the present day. If the 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight formula were applied, the 70 grams of prescribed protein would be more befitting of a man weighing 195 pounds. However, it would match the suggestion of 1.2 grams of protein per kilogram.

Over the years, protein ranges have been a prevailing concern that consuming high quantities of protein would eventually lead to health problems. For instance, in April 1993, famous British health columnist Dr. Vernon Coleman published a list of reasons why people would not consume too much protein.

Among the list of claims Coleman made were the following:

-

The overconsumption of protein would result in the protein being converted into body fat.

-

Eating too much protein would accelerate the body’s loss of calcium.

-

Consuming a lot of protein would strain the kidneys

-

Large quantities of protein could lead to the development of vitamin deficiency.

-

Too much protein could result in an increased risk of heart disease.

Decades later, we know that nothing on this list of concerns is fundamentally true, and those with a hint of truth were dependent upon the consumption of specific types of protein, and usually protein from high-fat animal sources.

Specifically, eating too many calories will result in those calories being converted into body fat in general, but lean protein has a very low likelihood of contributing to a caloric abundance. Further, only highly acidic protein sources with high fat quantities have shown a tendency to contribute to the excretion of calcium, while some studies have indicated that protein intake actually increases the rate of calcium absorption. (1)

With respect to kidneys, the preponderance of the evidence shows that only certain types of protein taken in high quantities have been shown to stress your body’s natural filtration system, with protein from meat sources being the most likely to pose a problem. (2) Despite this finding, there is little to no evidence that high protein intake is harmful in healthy individuals.

In fact, a meta analysis conducted by the Journal of Nutrition that evaluated the effects of 28 qualifying studies of more than 1,300 participants found that there were no adverse effects caused by high protein diets to human kidneys. (3) Therefore, there is no inherent health risk to your kidneys if you were to consume protein in daily quantities of 200 grams or more, provided that the source of the protein is safe.

Clean Food Label Project

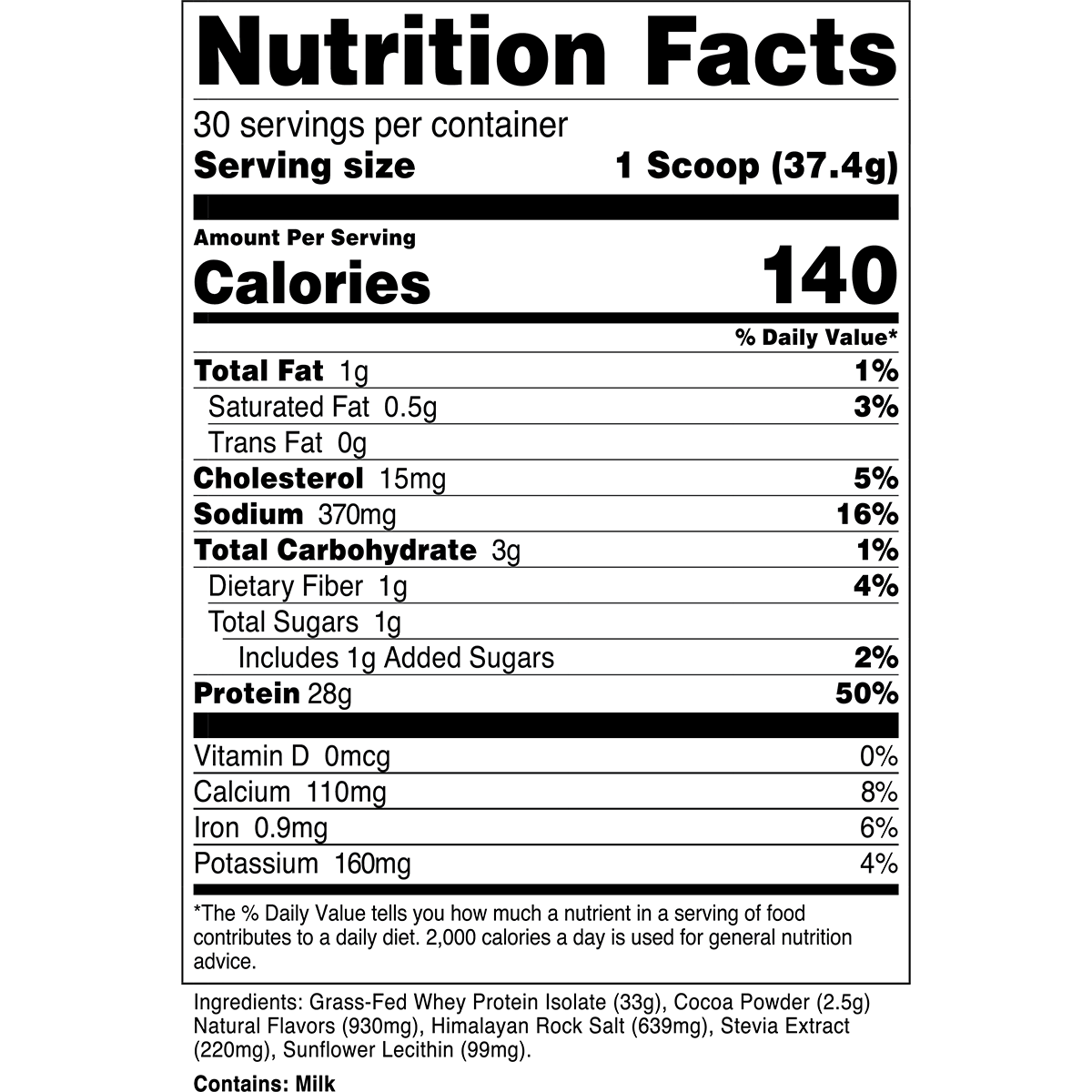

When it comes to the safety of supplemental protein, the general quality of protein supplements is seldom addressed. Yet, it becomes an essential talking point the more the conversation turns toward the consumption of increasingly greater quantities of protein powder and other protein supplements.

For example, if a protein powder contains contaminants, tripling the daily dose of that protein powder from 30 grams per day to 90 grams per day clearly results in the tripling of the contaminants that are being consumed. This is harmful enough in young adult populations, but older adults and aging populations that are already suffering through a decline in functionality will be less likely to isolate the causes of their health issues to hidden contaminants.

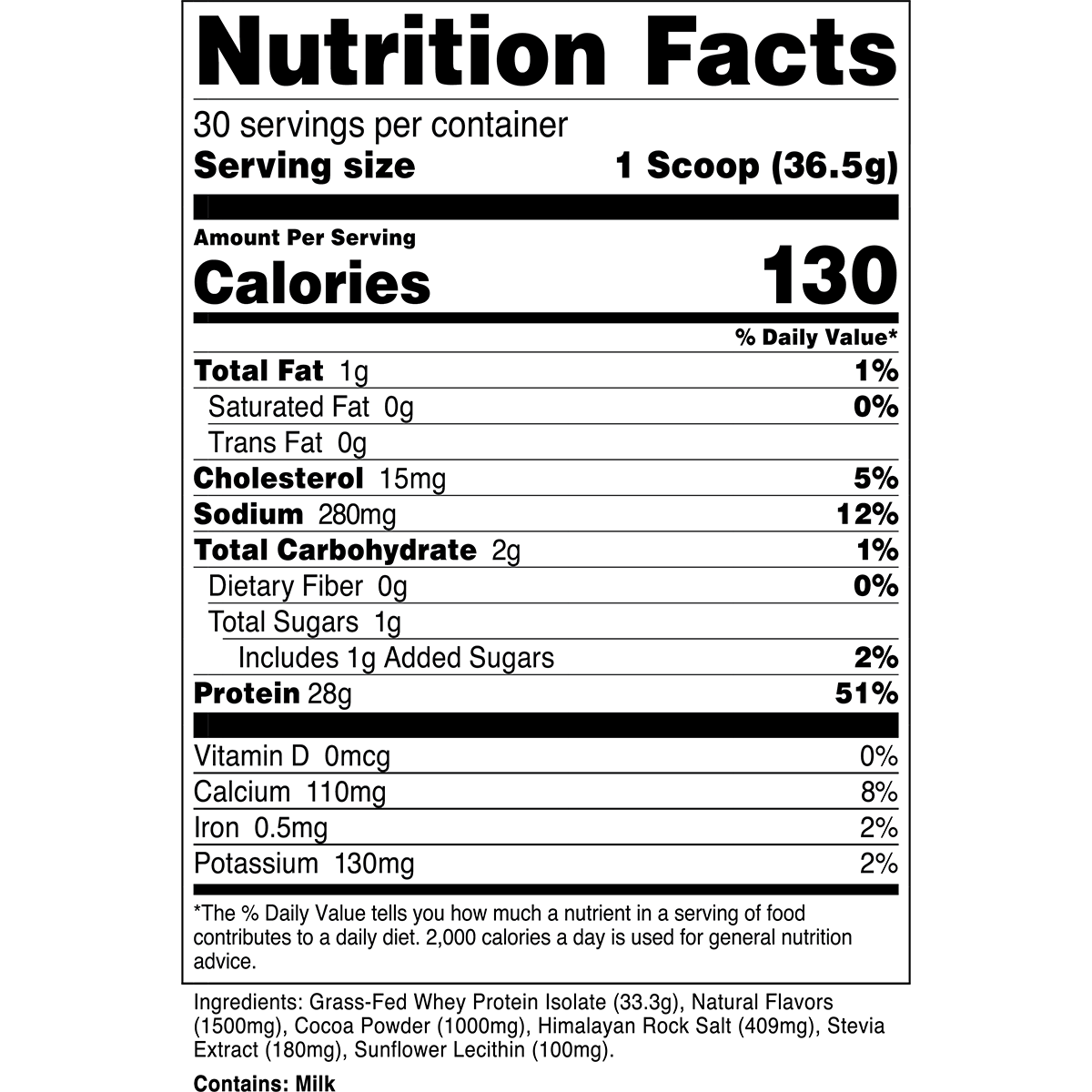

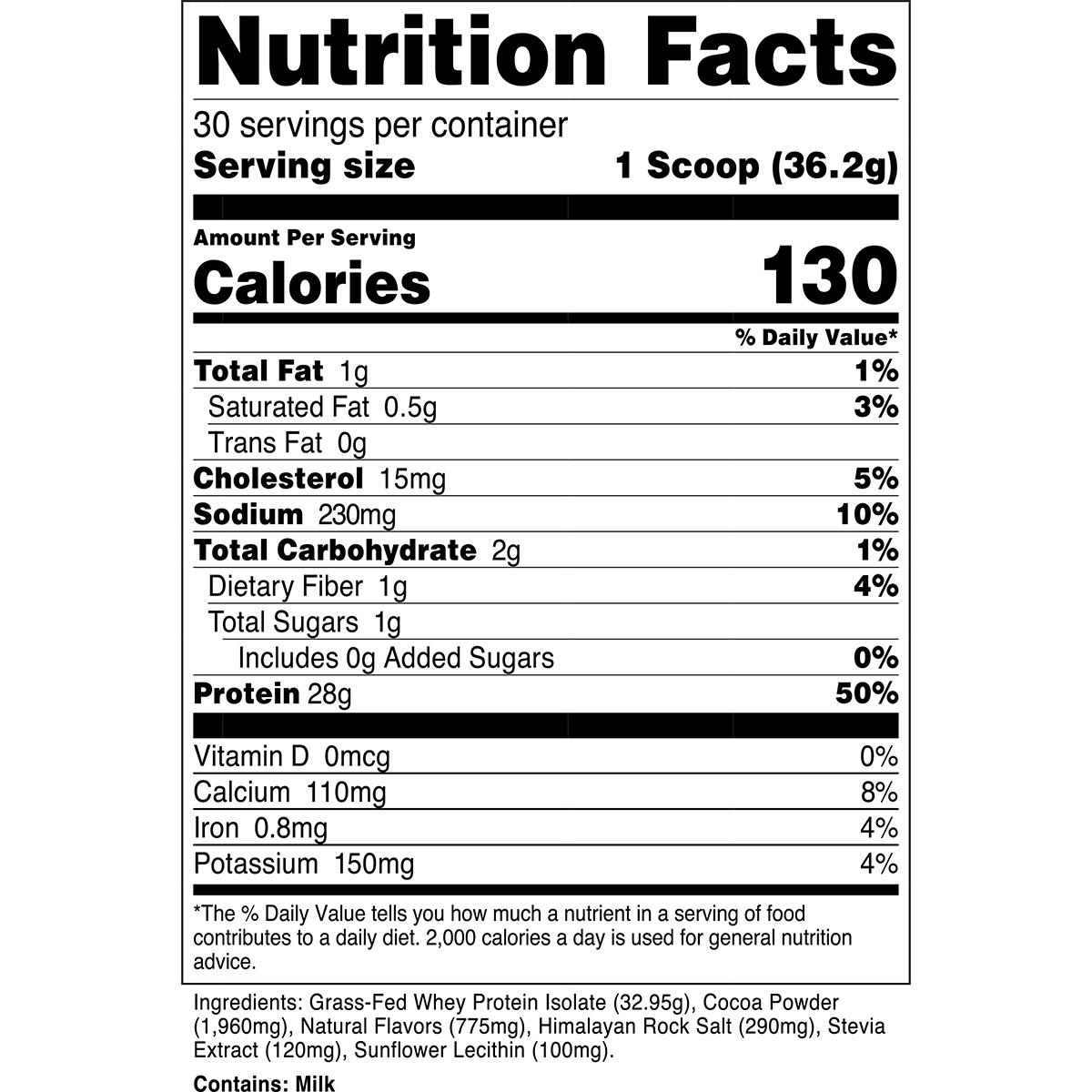

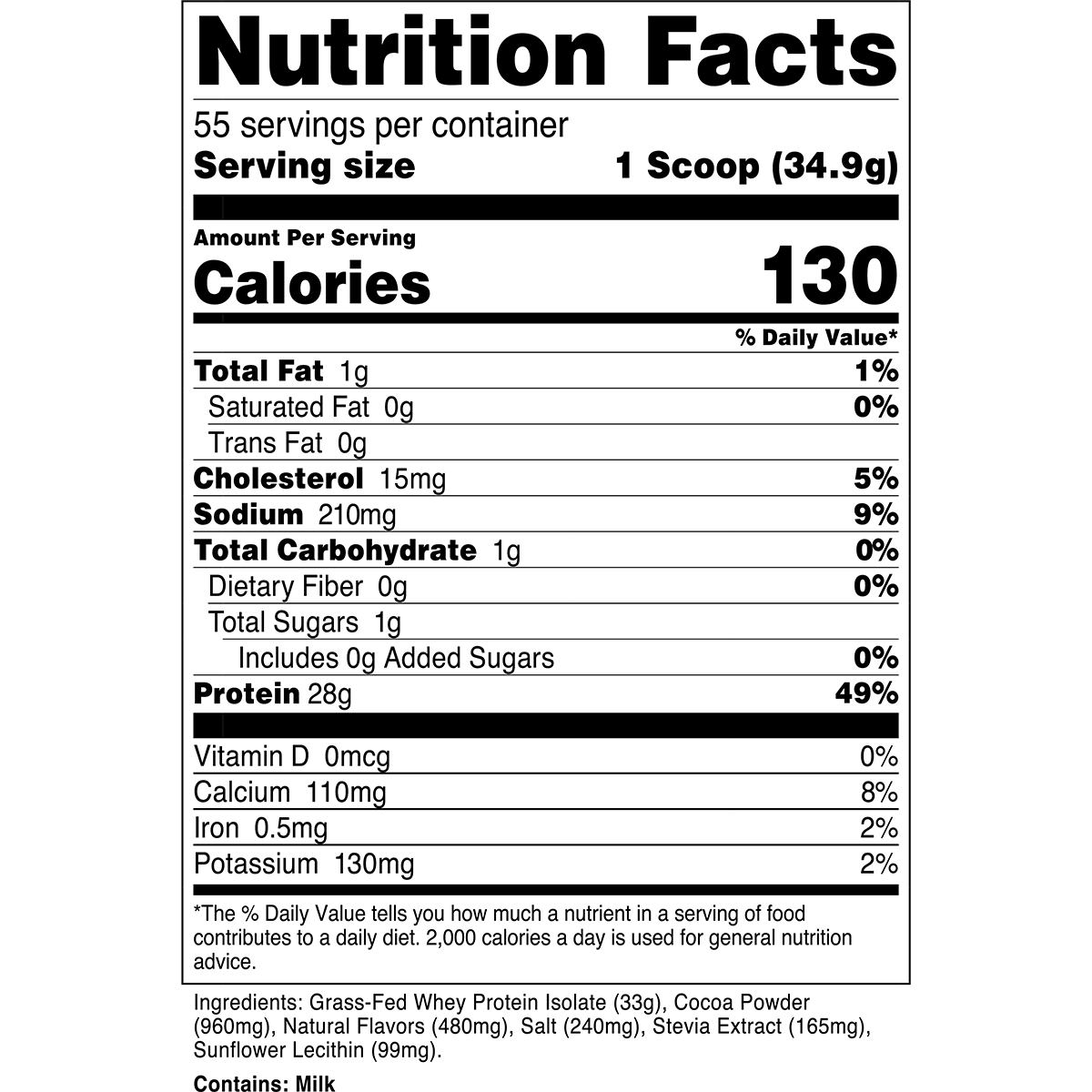

According to the 2025 Clean Label Project report, a shocking number of the top protein powders contain contaminants like lead, cadmium, and mercury. Of the 160 powders tested, 47 percent tested positive for toxic metals, while 21 percent tested positive at a rate of double the minimum threshold for lead.

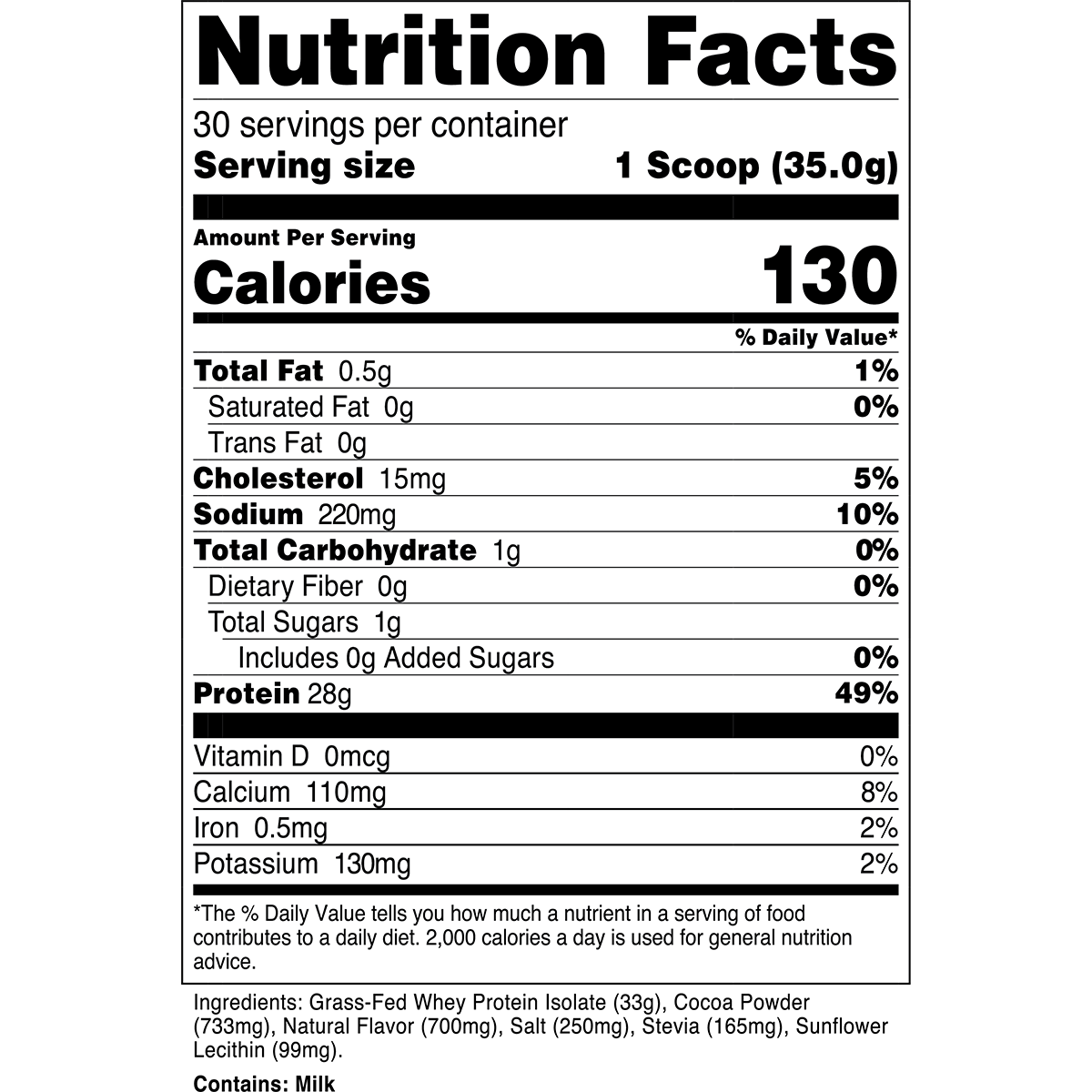

Adding to the surprise was the fact that the level and spread of contamination was partially dictated by the flavor of the protein, and the method of its production. Most notably, chocolate-flavored protein powders tested positive for contaminants at a rate of 65 percent, while a staggering 77 percent of plant-based protein powders and 79 percent of organic protein powders tested positive for lead. This latter statistic was presumed to be owed to the manner in which organic protein powder is produced, including the soil that plant-based organic powders were likely to be grown in.

The reason this matters is because recommendations to increase total supplemental protein may drive you toward the consumption of larger quantities of dangerous contaminants if you don’t ensure that you’re acquiring your protein from a safe source.

Making it Simple

The following table simplifies the process of providing you with guidelines with respect to how much protein your body requires as you age. While it incorporates the RDA guidelines proposed by The Food and Nutrition Board, it also recognizes the general safety of protein, and acknowledges the increased protein needs of adults as they age.

|

Age |

Standard Protein Intake |

Athletic Protein Intake |

|

18 - 40 |

0.8 grams per kg |

1.2 to 2.0 grams per kg |

|

41 - 50 |

1.0 grams per kg |

1.4 to 2.0 grams per kg |

|

51 - 60 |

1.2 grams per kg |

1.6 to 2.0 grams per kg |

|

61 - 64 |

1.4 grams per kg |

1.6 to 2.0 grams per kg |

|

65 and up |

1.6 to 2.0 grams per kg |

1.6 to 2.0 grams per kg |

Please keep in mind that this table is a general guideline, and it assumes that you have no health concerns that might make this recommendation problematic. As always, you are strongly encouraged to consult a physician or a dietary professional when making any significant changes to your nutrition plan.

Preparing for the Inevitable

The ultimate takeaway here is that a high protein diet is almost always to your benefit, and even more so as you age. Even though such a diet is essentially an option as you enter adulthood, it becomes a borderline necessity as you pass the age of 65. With this in mind, unless you have a specific health concern that prevents you from doing so, it can be said that the best way to prepare yourself for the pattern of protein consumption you’ll be required to adhere to in old age would be to begin adopting that standard now.

Sources

-

Darling AL, Millward DJ, Lanham-New SA. Dietary protein and bone health: towards a synthesised view. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2021;80(2):165-172. doi:10.1017/S0029665120007909

-

Ko GJ, Rhee CM, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Joshi S. The Effects of High-Protein Diets on Kidney Health and Longevity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020 Aug;31(8):1667-1679. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020010028. Epub 2020 Jul 15. PMID: 32669325; PMCID: PMC7460905.

-

Devries MC, Sithamparapillai A, Brimble KS, Banfield L, Morton RW, Phillips SM. Changes in Kidney Function Do Not Differ between Healthy Adults Consuming Higher- Compared with Lower- or Normal-Protein Diets: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Nutr. 2018 Nov 1;148(11):1760-1775. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy197. PMID: 30383278; PMCID: PMC6236074.